Pre-WWII CAS Posture and FM 31-35

Abstract

This article is the first in the “WWII TACP Origins” series. It covers the pre-WWII air power landscape and the Army Air Corps/Army Air Forces’ attitude toward close air support. Additionally, this article explores the original doctrinal publication to which the TACP career field can trace its conceptual origin. The 1942 edition of Field Manual 31-35 Aviation in Support of Ground Forces defines the Air Support Party and Air Support Officer, the predecessors to the Tactical Air Control Party and Air Liaison Officer. Pictures are at the bottom of the article, and the full 1942 FM 31-35 can be found here.

Pre-WWII CAS Landscape

Most current and former Airmen alive today, even TACPs, assume late dates for the origins of TACP and close air support in general. Most assume that close air support as we know it began in the Vietnam Era. The Army Air Corps developed the first comprehensive close air support system during the interwar period between WWI and WWII. During the First World War, the assumption was that the whole purpose of airpower was to act as an auxiliary to ground forces. In their slow, short-range, and vulnerable aircraft, pilots could adjust artillery, collect intelligence, and possibly support ground forces via gun runs or dropping small bombs or hand grenades out of their open cockpits. Few imagined that the airplane could overtake an army as the primary mechanism for defeating an enemy.

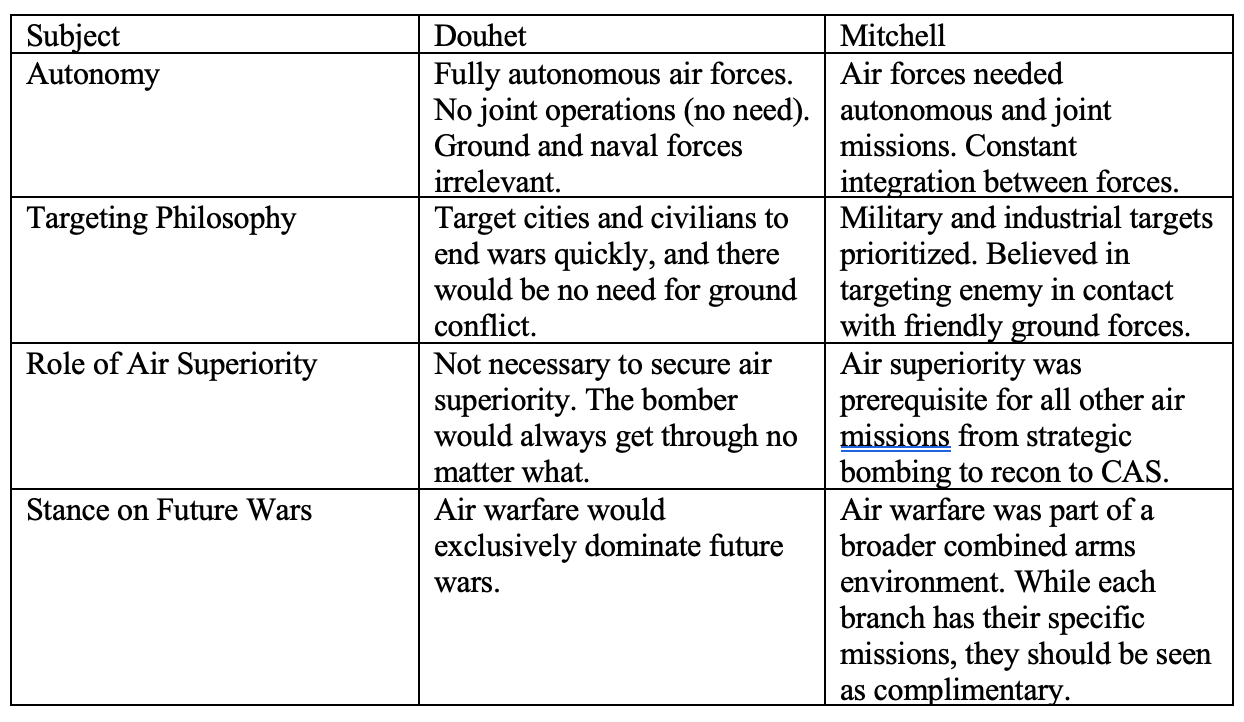

Two visionary leaders imagined a future where fleets of large, long-range bombers would be key to winning the next war. Their ideas influenced American air leaders between World War I and World War II, who developed a strategic bombing theory that shaped how the United States and Britain fought against the Nazi regime. The Italian Fascist Giulio Douhet and the American General Billy Mitchell are typically referred to as the two main influencers of American strategic bombing theory in WWII. In reality, the US Army Air Corps adopted an airpower strategy that almost exclusively aligned with Douhet while a select few fought for an air arm that resembled Mitchell’s vision.

Douhet believed in an independent air force that would be so dominant that it would never need to integrate with ground or naval components. He imagined that bombers, defended by onboard gunners, would “always get through” to their targets and that by bombing civilian populations, the opposing force would become devoid of morale and simply give up. Mitchell disagreed, believing in the supremacy of combined arms – that air, ground, and naval power could complement each other. For example, if the air force provided close support to an army, then that army could more efficiently take and hold land that could be used for forward air bases.

Table 1: Core differences in Douhet and Mitchell's airpower theory. It can be summed up as such: Douhet believed in the total dominance of air power and that traditional military power structures were a thing of the past. Mitchell believed in an integrated military where air, land, and naval powers supported each other.

In the late 1930s and into 1940, most air leaders were itching to separate the Army Air Corps from the Army and create their own autonomous branch of service. To their dismay, they had no justification for an independent air force since no air force had yet proven to be the dominant force in battle. In fact, the Germans had shown the world the efficacy of combined arms through the combination of dive bombers and armor in a style of warfare they dubbed Blitzkrieg. Nonetheless, air leaders sought to prove that airpower could win wars on its own if called to action in Europe, thus developing an air power attitude resembling Douhet.

As the United States began developing strategies to potentially use against the Nazis, they found a middle ground between those who argued for a purely Douhet-style air force and one that resembled Mitchell’s combined arms theory. In 1941, the Army Air Corps was rechristened as the Army Air Forces (AAF), providing the air arm with a larger, more independent force structure. The creep toward independence led to a force that was primarily strategic-bombing-minded. The AAF entered WWII with a strategic and independent attitude, and its leaders saw support for ground forces as a waste of precious resources.

However, the AAF’s subservience to the Army forced a level of integration and support to ground forces, and a few air leaders were genuinely passionate about the three tactical air missions – air superiority, interdiction, and close air support. These Mitchell-minded leaders included American Generals Elwood “Pete” Quesada, Otto P. Weyland, and Carl “Tooey” Spaatz. These were heavily influenced by similarly attuned British leaders like Air Marshall Arthur Tedder (Mediterranean Air Command CC) and Air Marshall Arthur “Mary” Conningham (Western Desert Air Force CC). The “Arthurs” were arguably even more staunch than Mitchell when it came to tactical airpower, and their methods rubbed off on the American tactical airpower advocates in the Northwest Africa Campaign.

FM 31-35 Aviation in Support of Ground Forces

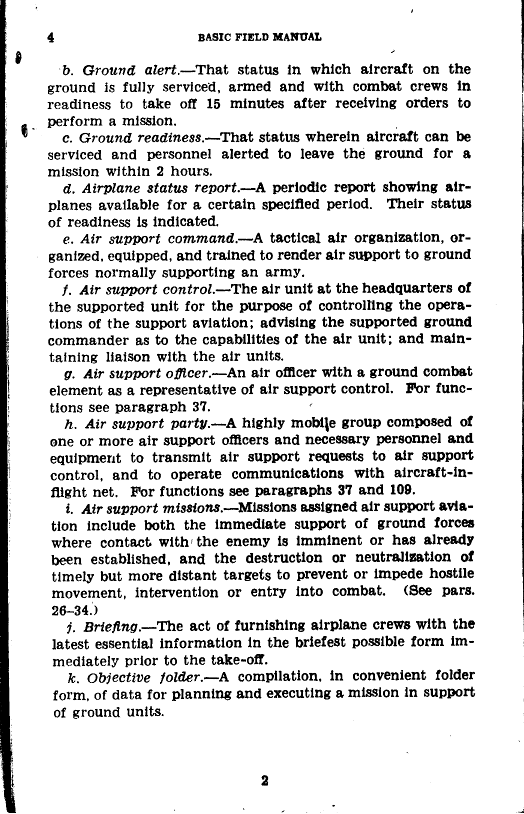

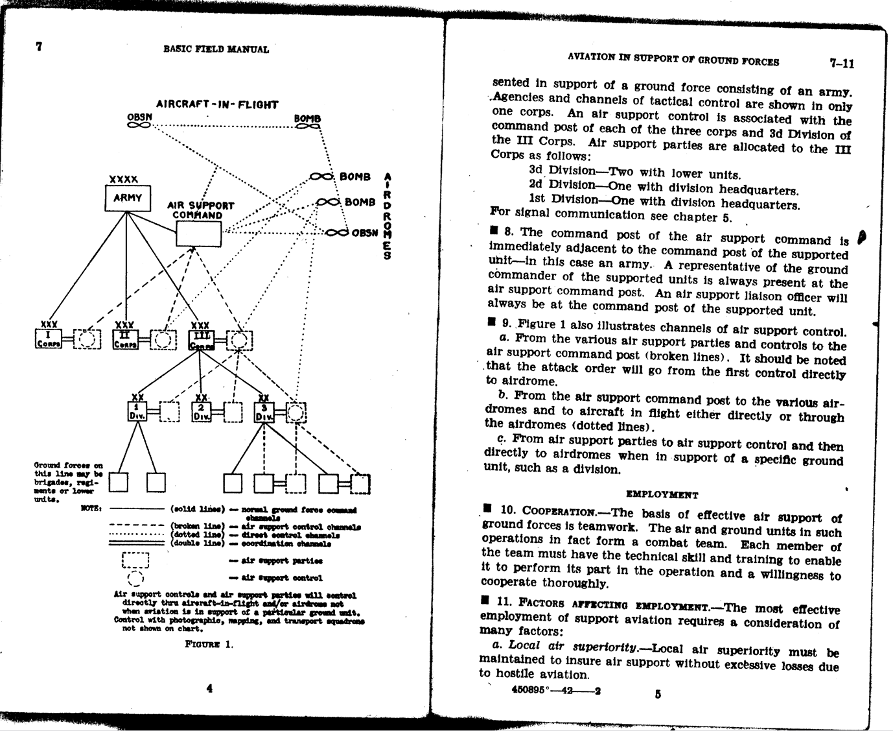

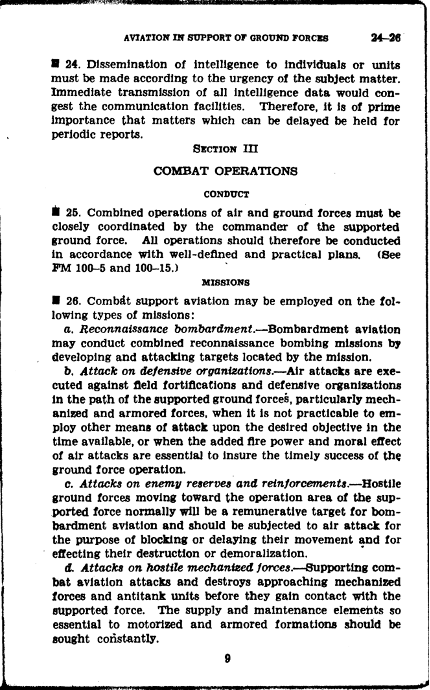

In 1942, the Army published a pivotal document that forced the AAF to support the Army Ground Forces (AGF). This document outlined the roles and responsibilities of air and ground players for joint integration. For the purposes of TACP history, the predecessor to the TACP was explained in FM 31-35. The field manual defined the Air Support Officer, Air Support Party, and the types of air support missions. Each of these definitions evolved with the war in the European Theatre and, in the 1946 FM 31-35 rewrite, were redefined as Air Liaison Officer, Tactical Air Control Party, and close air support.

It is important to remember that in 1942, the American military had no experience with these concepts. They had modeled FM 31-35 on theory and on what had worked so well for the Germans in their 1939 and 1940 Blitzkriegcampaigns. There was one major change from the German model. As shown in the Battle of Britain, dive-bombers were proven useless in contested airspace. As the AAF prepared to perform close air support in WWII, leaders believed the best vehicle for ground attack would be medium and light bombers. They also believed that the best method of command and control for CAS was to divvy out squadrons to division commanders so they could have a constant “air umbrella” over their units. Aviation in Support of Ground Forces reflected those beliefs. The AGF and AAF were in for a rude awakening on the practicality (or lack thereof) of those concepts when they began their soft start to the war in North Africa.

Nonetheless, FM 31-35 set a precedent for many important aspects of close air support and air-ground coordination. It laid the foundation for a Tactical Air Control System (later changed to Theatre Air Control System), a communications network, and a culture of air-ground cooperation. Most importantly, the foundational doctrine laid out in the 1942 FM 31-35 set the stage for the partnership of Generals Omar Bradley and Pete Quesada, who created the Armored Column Cover concept together. Later, the partnership of General George Patton and General Weyland resulted in the perfection of that concept for the rest of the war in the ETO. First, the system had to undergo a trial by fire against the Nazi occupation of Libya.

Author’s Note

See the below pictures for more details on the 1942 FM 31-35. The next article will cover close air support and the performance of the Air Support Party, the predecessor to the Tactical Air Control Party, in the Mediterranean Campaign. Email nbachand@tacpf.org for questions or comments.

Figure 1: Definitions of Air Support Officer, Air Support Party, and Air Support Missions. Note: In WWII, close air support was generally referred to as close support, immediate support, armored column cover, airborne troop support, or support for troops in contact.

Figure 2: Pages four and five outline the first iteration of the Tactical Air Control System (TACS, later known as Theatre Air Control System).

Figure 3: This page is a good example of the types of ground support missions in WWII and how they thought of the role of airpower in the ground scheme.

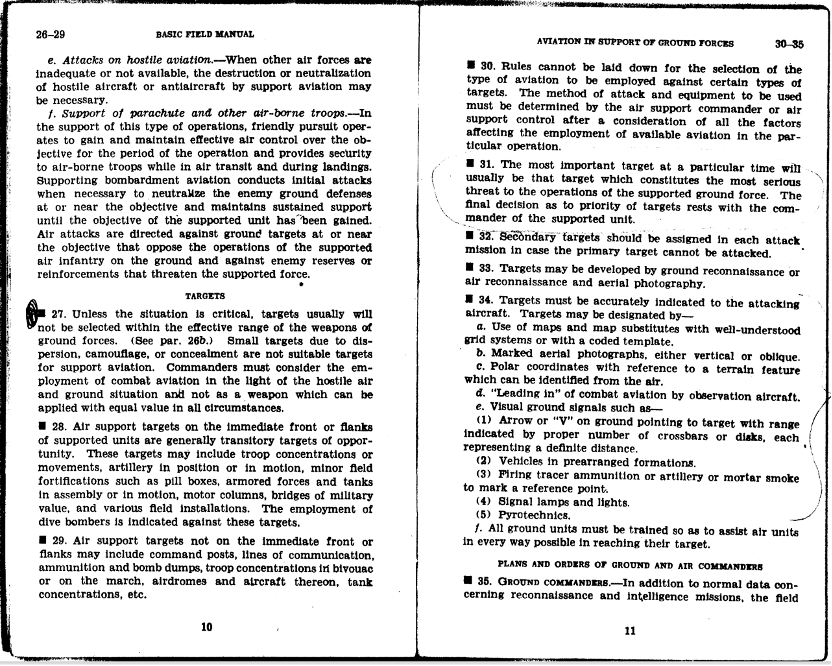

Figure 4: Note the types of targets thought to be suitable for CAS before the war. This drastically changed during and after WWII. Also, note the marking types on page 11.

Figure 5: The Douglas B-23 Dragon, a medium bomber thought to be suitable for CAS before first contact in Africa, its inability to survive at low altitude negated any effectiveness in contested airspace

Figure 6: The Douglas A-20 Havoc was a light bomber that suffered similar downsides as its medium counterparts.