Author’s Note: This article is an extension of the previous article. It covers the use of CAS by “Lightning” Joe Collins and revisits the XIX TAC/Third Army partnership in the Battle of the Bulge. Research on the actions of individual Air Support Parties during this period is still in progress, forcing this article to revolve more around CAS partnerships. The most specific information on air support parties comes at the tail end of this article. When ongoing research is concluded, this time period will be revisited through the ASP lens.

Before the D-Day landings, General Eisenhower needed a new commander for First Army’s VII Corps. General Bradley nominated a former West Point classmate known for aggression and loyalty, Joseph Lawton Collins, who later became “Lightning Joe Collins” and rose to the rank of Chief of Staff of the Army. After a strong showing on D-Day, Collins quickly became a favorite attack dog for almost every Allied commander, most notably Bradley and Field Marshall Montgomery. Collins next found himself leading at the front during Operation Cobra (see WWII Origins #3), where his VII Corps leaned on what he dubbed Forward Air Support Parties (FASPs)[1] to direct P-47s for close air support, enabling his corps to not only push the Germans out of the Falaise Pocket but to blast his entire corps through the pocket in pursuit of a reeling defending force.

Lightning Joe earned his nickname for his aggressive, rapid movements in the Pacific Campaign before he brought a similar mindset to VII Corps in the European Theatre. He found that the CAS system devised for the European Campaign suited his preferred strategy and put it to use early and often. After blowing through the Falaise Pocket and a swift capture of France, Collins’ VII Corps was tasked with taking the first German city of the war at Aachen. [2] Aachen, a great case study for CAS in urban warfare (for those who don’t care to preserve infrastructure), was initially a daunting task for Collins and IX TAC thanks to new German tactics for camouflaging vehicles, moving only at night, and staying off roads completely. This new challenge made interdiction a non-factor going into the battle.[3]

Lightning Joe Collins, “The General who made a name for himself in two theatres”

Collins devised a pincer movement with the 1st Infantry Division to the North and the 30th Infantry Division to the South, with heavy CAS and artillery support for both divisions. Collins relied heavily on support from Quesada’s IX TAC for CAS in close engagements, controlled by an ASPO at the front lines with the callsign “Sweepstakes.” At the same time, artillery bombarded deeper positions, most often directed by airborne air support party officers or reported by P-47 pilots during debriefs. The strategy worked as expected for Collins, with the most challenging aspect of the defense being pillboxes and bunkers, both dealt with primarily by P-47s directed by an air support party. The battle lasted from October 2nd and ended on October 20th, with the Allies taking 5,000 casualties and the Germans taking 7,000 casualties and 5,600 prisoners. With close air support, air support parties, and the P-47 as the decisive factors in the battle, Lightning Joe took the first major German urban area in less than a month.

The German city of Aachen in the aftermath of the battle.

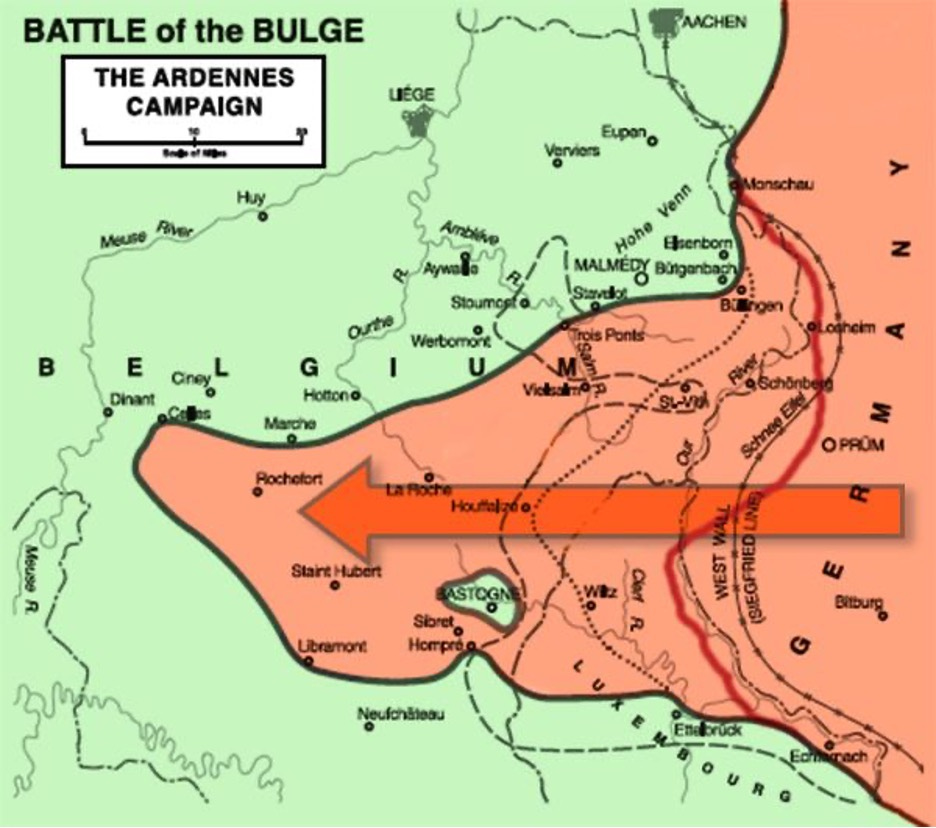

Collins’s VII Corps and the rest of 1st Army weren’t so fortunate to use American Blitzkrieg tactics through the Hurtgen Forest on their way to the Siegfried Line. Although support from IX TAC helped 1st Army to push through the Ardennes, it was a grind. Instead of blasting through tens or hundreds of miles of German lines a day, miles eastward per day could be counted on one hand, with movement coming to a complete halt along the Siegfried Line come December. Then, on December 16th, during a period of bad weather that disallowed Allied close air support, the Germans sprung a massive 400,000-man, 1,200-tank, 4,000 counterattack. That counterattack created the bulge in the 80,000-man Allied front line for which the Battle of the Bulge earned its name. With much of the 1st Army now encircled and entrenched in isolated cities, General Bradley called on Patton’s 3rd Army and Weyland’s XIX to launch a logistically ambitious counterattack from the South.

Patton and Weyland’s forces were recovering from their November capture of Metz (which they had taken in a similar fashion to Aachen) and preparing to continue a rapid march eastward. Instead, Patton was tasked to immediately begin moving his entire Field Army 100 miles North to Bastogne, during winter, with questionably sufficient food, fuel, and ammunition reserves. Patton’s “90-degree pivot” is considered one of the most impressive feats of military logistics and operational flexibility in modern warfare. Patton ambitiously promised that he could get his forces (133,000 troops and 44,000 vehicles) to the besieged 101st Airborne Division defenders at Bastogne in 48 hours, requiring multiple divisions to disengage from active combat, reposition for movement North, and prepare for engagements from the North and the East along icy roads.[4]

An illustration of the bulge. Note the encircled Bastogne that never left 101st ABN DIV’s occupation

From December 17th through the 23rd, IX TAC continuously attempted to get some fighter-bomber effects around Bastogne with the SCR-548/MEW radar, but to limited effect.[5] The same could be said for the XIX TAC-provided CAS for Patton’s march North. With the poor weather, there was very little the 9th Air Force could do to assist in breaking the siege other than one-off strikes to attempt to keep the German attackers at bay. [6] On December 20th, Patton’s lead element, the 4th Armored Division, made first contact with the Germans in the bulge, leading to intense fighting with the weather still limiting CAS capabilities.

Just days before Christmas, a reporter from Pennsylvania asked around near the front if there were any Philadelphians nearby who wanted a letter home printed in the newspaper. One soldier handed him a slip that read, “For Christmas, I want some good weather so the fighter-bombers can come give us a hand.”[7] The soldier’s Christmas wish came true, and on Christmas Eve, the weather finally cleared enough for the fighter-bombers to start softening up the German front. When the TACs could contribute to the fight, Allied ground units defending the areas encircled by the Bulge were in rough shape.

At the end of December 24th, a First Army aide reported, “Despite the air’s magnificent performance today, things tonight look, if anything, worse than before.”[8] While this statement turned out to be an exaggeration, it represented the chaotic state of the Battle of the Bulge at that time. Bradley was ill-informed of the state of 12th Army Group subordinates, Patton hadn’t moved up to relieve pressure from Bastogne as quickly as he wished (thanks to the weather limiting XIX TAC), and Field Marshall Bernard Montgomery was trying and failing to take matters into his own hands behind Bradley’s back.[9] As hectic as the situation was for the Allies, they were sewing just as much chaos for the Germans and planting the seeds for success in the coming days. The 101st Airborne held Bastogne, Allied lines were holding around the Meuse River, and tactical air power began cutting off the German supply lines, intensely exacerbating an already existing limiting factor for the German offensive.

By the time Thunderbolts had entered the Battle of the Bulge, a nearly complete German breakthrough had essentially been removed from the table. In December, the American CAS system grew even stronger as the Allies had six months of fine-tuning an already effective system. The main improvement was the timely notice of air support allocations. One of the complaints of 9th Air Force leadership until then was the Army’s ground forces’ inability to rapidly leverage the advantages given to them by successful CAS sorties. Ground force commanders responded that they had difficulty acting on their close air support because they had not been notified during the planning phase that they would receive it. They often didn’t know if a request had been approved or denied until fighting already started.

By December, Allied communications structures had become much more solidified, including a robust telephone and teletype network. Enhanced communications meant that the enfeebled defenders of the Ardennes and Third Army reinforcements would be notified on December 24th and 25th that they were receiving CAS and could plan rapid troop movements accordingly. On the other side of the communications network, Ground Liaison Officers provided more timely ground force locations and targeting data during their pre-flight briefing to the fighter-bombers.[10] Even marking techniques had improved. Quesada remembered, “Another good idea came from our ground troops – putting colored panels on top of the tanks. Pilots could see the panels and knew those tanks were ours. The Germans caught on and began using the same color. So our tank forces changed colors every day. The panels were a lifesaver for our tanks in the winter. During the Battle of the Bulge the panels were especially valuable.”[11]

On top of the communications advancements leading up to December of 1944, the execution of CAS by forward-controlling ASPs had become much better. Of the performance of the ASP, 12th Army Group concluded that “Ground direction of aircraft to targets is extremely effective and does not mean loss of flexibility or air force control. On the contrary, it increases flexibility by permitting the instant use of firepower by a forward battalion without curtailing the ability of the fighter control center to assume all control over all aircraft practically instantaneously.”[12] Therefore, when fighter-bombers entered the fray, they were well-rested, the aircraft were nearly perfectly maintained, they had excellent situational awareness of the battlefield, ground forces knew when and where they would come to the rescue, and the ASPs were primed to execute.

A destroyed German tank near Bastogne

It is noteworthy that on December 25th, the credit for the mass destruction of the German attackers belonged to the American Army apparatus as a whole, not just the fighter-bombers or other tactical air power functions. Close air support played a significant role in the Allied success on Christmas Day. Still, it was clearly bolstered by the Third Army's maneuver from the South, the movement of artillery within range of the Germans, and the sheer grit the 101st showed in defending their areas from their foxholes with machine guns and bazookas against tanks. In this way, the successful breaking of the German offensive in the Ardennes showcased effective American combined fires and coordinated movements, with close air support as a significant component in a well-rounded fighting machine. The response to the Battle of the Bulge is a model of joint operational flexibility and highlights the effectiveness of combining ground and air power at the front lines.

On December 26th, elements of the 4th Armored Division finally broke through German lines, defeated the siege, and relieved the 101st Airborne. The 12th Army Air Effects Committee wrote in July 1945 that, “To assist in the ground action, it is felt that invaluable contributions were made by fighter bomber, tactical reconnaissance, and medium and heavy aircraft. Fighter bombers were used effectively on close-in missions, on armed reconnaissance, and on day and night fighter sweeps. Bombing and strafing near the front were well handled in attacks on assaulting units, tanks, enemy artillery, and reserves.” The author added in the conclusion that, “In the defensive situation the effectiveness of the fighter bomber, the tactical reconnaissance aircraft, and the medium and heavy bombers proved to be a necessary adjunct to an all-out effective counter-offensive.”[13] In other words, the After Action Report for the Battle of the Bulge named close air support the decisive factor for one of the most critical battles of the entire war.

Thus, the massive last-ditch counterattack was defeated by fast-moving American ground forces aided significantly by close air support and artillery. Hitler ordered his now rag-tag group of surviving units to reassemble and make another push, but by the 26th, the result of the Battle of the Bulge was a foregone conclusion. It was only a matter of time before the Allies massed for a push to the East. Such a push occurred on January 2nd, and though disorganized and frantic amid some strange political battles, the Allies had fully restored the original front by January 16th. By the end of the Battle of the Bulge, the Allies suffered roughly 75,000 casualties while the Germans suffered approximately 100,000 and the complete destruction of some of its most valuable armored units (the Panzer Lehr Division and the 5th SS Panzer Army).

Author’s Note: There’s A LOT more to get into here. If interested, see the WWII chapter in my dissertation on the TACP Foundation Website.

[1] It’s important to remember that although the ASP/Rover system was tested and proliferated as early as the Mediterranean Campaign, it was still new. The system was called different names and functioned differently across field armies and even corps.

[2] In fact, the Allied front line moved so quickly through France, that when IX TAC P-47s moved to captured airfields, they consequently moved too fast for their logistics to keep up, leaving them flying CAS missions without 1,000, 500, or 250lb bombs. Robert V. Brulle, Angels Zero: P-47 Close Air Support in Europe. 42-43.

[3] Ibid., 44-45.

[4] Antony Beevor. Ardennes 1944: The Battle of the Bulge. (New York, NY; Penguin Books, 2015), Introduction.

[5] The MEW was an early attempt at a ground controller directing a fighter bomber attack an area based on radar vectoring.

[6] John Schlight. Help From Above: Air Force Close Air Support of the Army, 1946-1973, 47.

[7] IX TAC, and Elwood “Pete” Quesada. Achtung Jabos: The Story of IX TAC. Starts and Stripes, G.I. Stories Series. Paris, 1945.

[8] Antony Beevor. Ardennes 1944: The Battle of the Bulge, 270.

[9] Ibid., 270-280. Beevor has extensive commentary in Ardennes 1944 on the havoc caused by Montgomery’s political maneuverings and attempts to take control of all Allied forces during the Battle of the Bulge.

[10] 12th Army Group. Immediate Report #1, Close Air Support Within Twelfth Army Group. November 1944. (Call # 502.4501-1 in the USAF Collection, DAFHRA, Maxwell AFB, AL), 4-5.

[11] Air Force Historical Foundation, Jacob L. Devers (Gen., Ret.), and Elwood R. Quesada (Gen., Ret.). Impact, The Army Air Forces’ Confidential Picture History of WWII No. 7: Tactical Air Power: Cutting the Enemy’s Arms and Legs. (James Parton and Company, New York, 1980. Call # 168.7144-10 in the USAF Collection, DAFHRA, Maxwell AFB, AL), xvi.

[12] Ibid., conclusion.

[13] 12th Army Group, Air Effects Committee, and Omar Bradley. Effect of Airpower on Military Operations. July 15th, 1945. 150-151.