D-Day, St. Lo Breakout, and Armored Column Cover

Planning for close air support proved challenging for tactical air commanders and ground commanders, especially given the perceived challenges of executing the largest amphibious assault of all time against heavily fortified beaches. The highest levels of Allied leadership, namely Generals Eisenhower, Bradley, and Quesada on the American side, alongside Montgomery, Tedder, and Conningham on the British, recognized the near impossibility of providing on-call (immediate) close air support to the beach assaults. Thus, D-Day planners decided to run with an air support plan consisting mostly of interdiction and pre-planned close air support, with Air Support Parties (ASP) co-located with the landing craft to provide on-scene coordination. In all reality, that on-scene coordination between pilot and ground controller wasn’t complicated – pilots simply needed to target the most relevant defensive positions on the cliffsides without harming Americans on the beach and confirm with a Rover that Americans weren’t in the target area. Given the relative simplicity of targeting and the shocking absence of Luftwaffe resistance on June 6th, 1944, preplanned close air support and interdiction missions went surprisingly smoothly for such a complex operation.

The main friction point for the ASPs was the lack of communications with higher headquarters to request on-call close air support. The communication network consisted of cumbersome HF communications to naval vessels, who then relayed messages to the 9th Air Force and IX Tactical Air Command (IX TAC) Air Support Center in Uxbridge. As it was, the ASPs used HF radios too weak to even reach the communications relay ships, and the ASC only processed three on-call close air support missions on D-Day. Nonetheless, the plan to rely on heavy amounts of preplanned close air support paid off enough to make up for the lack of on-call capability.

The real challenges and accomplishments of close air support and the air support parties came shortly after D-Day during the struggle for the Allies to break out from the Cotentin Peninsula. General Omar Bradley, during June the First Army commander and primary operational decision-maker for the US Army, formed a cohesive personal and professional bond with his tactical air counterpart, General Pete “Elwood” Quesada. It’s worth mentioning that between the Mediterranean Campaign and D-Day, the AAF reorganized its numbered air forces to operate by function. In Europe, this meant that 8th Air Force was solely responsible for strategic bombing and the 9th Air Force became the chief tactical air arm. Thus, 9th Air Force subordinated three tactical air commands (TACs), the IX, XIX, and XXIX TACs in support of the three respective Field Armies subordinate to Twelfth Army Group (beginning August 1st). With only one primary field army in place from June through July 1945, First Army and IX TAC were the only active American units during the breakout period. Quesada, as the IX TAC commander, therefore handled all matters of interdiction and close air support for Bradley’s First Army.

Once the Allies secured a foothold on the Cotentin Peninsula, they famously struggled to break out from the hedgerows and past St. Lo. To break out, the Allies planned another massive interdiction campaign similar to the pre-planned fires on D-Day. This operation, dubbed Operation Cobra, combined the 8th and 9th Air Forces again for a massive attack on the St. Lo area. On July 24th, the 8th and 9th Air Forces began their preliminary bombing at St. Lo. Still, poor weather and planning resulted in a morale-devastating friendly fire incident that killed 25 and injured 300 American Soldiers, causing a delay in operations through the rest of the day.[1]

The fratricide could have been avoided had the Allies planned these strikes using Rovers or L-5 Horseflies to check aircraft in and provide last-minute coordination. Instead, planners at 8th Air Force treated the attacks similarly to strategic bombing in which the pilots are usually unconcerned with friendly forces on the ground. Fratricide was not an unforeseen consequence. Bradley and the British Air Marshall Leigh-Mallory (CFAAC) accepted the risk that came with allowing heavies to bomb near friendly lines, but Bradley became enraged when he discovered that the bombers had released their ordnance perpendicular to the front lines instead of parallel as had been planned.[2] There was little to no in-person coordination between AGF and 8th Air Force for the strikes, only telephone and teletype orders and instructions.[3]

Bombing resumed on July 25th, and 600 fighter-bombers from 9 AF continuously bombed a 300-yard area in St. Lo while 1,800 heavy bombers from the 8th AF carpet-bombed the area occupied by the Panzer-Lehr Armored Division. While the 9th AF fighter-bombers were successful in their attacks, the 8th AF heavy bombers again dropped some of their payloads on friendlies, killing 111 men and wounding 490, including Lieutenant General Lesley McNair.[4] McNair’s death marked the highest-ranking officer loss for the United States in the war, made worse by the fact that it happened by friendly fire. Nonetheless, the operation was an overall success, with the possibility of fratricide yet again an accepted risk with the decision to use the heavies. The next day, First Army pushed in to occupy St. Lo, and the breakout from the Cotentin Peninsula was secured.

Crucial to Cobra's follow-up success was the contribution of XIX TAC commander Pete Quesada and his advent of the Armored Column Cover (ACC) concept, first utilized on July 26th to tremendous effect.[5] ACC proved to be the crowning achievement of close air support in the war and should have been a case study in advancing close air support doctrine. It was a true example of US forces imposing their will on the Germans and forcing them to make the bad decision to retrograde or the worse decision to fight and die against an armor division supported by endless close air support.

The continuous cover of four P-47s over the armored column, controlled by an ASPO/Rover in the lead tank via radio, allowed the column to move very quickly as the Thunderbolts were able to rapidly strike any target in front of them. Through the combination of ACC and a ground controller in the lead tank, the Allies had perfected their version of Blitzkrieg with instant success.[6] On the advance of the US 3rd Armored Division from July 26th through 31st, flights of P-47s effectively struck targets in front of the tank advance with zero fratricides.

When there were no immediate targets for the Thunderbolts, they scanned the route of travel up to thirty miles ahead of the column to strafe and bomb artillery positions, machine gun positions, and hastily constructed defensive fighting positions. The shock of devastating strafing and bombing runs from the Thunderbolts followed by the shock of an untouched armored column following in its wake caused most of the Germans along the route to flee without a fight.[7] The method also harmoniously integrated the interdiction and close air support missions. By moving up and down the route of travel, the Thunderbolt pilots were constantly transitioning from CAS to interdiction, made seamless by radio communication with the Rover Joe in the lead tank.[8]

Quesada’s innovation on the use of P-47s for ACC was a monumental accomplishment for Allied close air support. Upon seeing the effects of armored column cover firsthand, Omar Bradley wrote, “For about two miles the road was full of enemy motor transport and armor, many of which bore the unmistakable calling card of a P-47 fighter-bomber – namely, a group of fifty-caliber holes… Whenever armor and air can work together in this way, the results are sure to be excellent… so long he (enemy armor) stays on the roads the fighter-bomber is one of his most deadly opponents.”[9] For the rest of the war, each Allied TAC and Field Army partnership mimicked that success to varying degrees. It produced the ideal relationship between air and ground forces, especially for highly mobile units like armored divisions or mechanized infantry. Given its reliance on on-scene coordination with previous flights and the ASPO, ACC exploited the inherent advantage of close air support and air power in general – its flexibility. The ASPO had the authority and capability to pick and choose targets on the spot, or to send the aircraft forward to strike deeper targets based on the on-scene commander’s intent. Using this methodology, Quesada and Bradley had achieved an unforeseen advantage of a synergistic air-ground partnership. It forced the German's hand into either committing to a defense, making themselves incredibly vulnerable to the P-47s, or dispersing as they did along the route to St. Lo, allowing Allied armored divisions to maneuver and take key ground.

On August 1st, 1945, the Allies took enough ground in France to bring to shore their full number of troops, requiring a reorganization of the Army. Twelfth Army Group was formed with Bradley at its head, General Hodges took his place as the First Army Commander supported by Quesada’s IX TAC. General Simpson led the Ninth Army supported by Nugent’s XXIX TAC. Arguably the most impactful partnership for the destruction of the Wehrmacht in the West was the introduction of Patton’s Third Army and his partnership with General Otto P. Weyland’s XIX TAC. Together, the two generals took the Rover Joe and armored column cover concepts, perfected them, and became famous for their shockingly fast destruction of every enemy force they encountered. This success was largely thanks to the close air support enabled by the Air Support Parties with front-line units.

Author’s Note: More to follow on Armored Column Cover in #4

Figure 1: A P-47 Firing Rockets

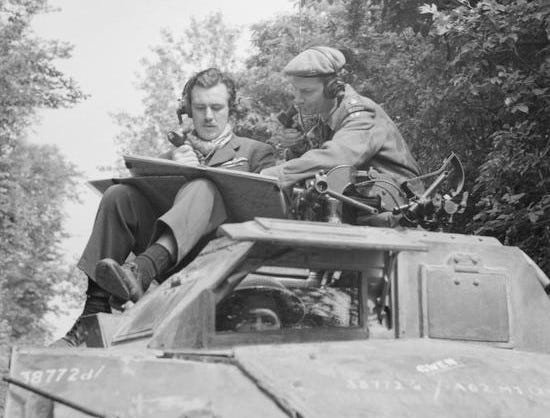

Figure 2: A British ASP/Rover team coordinate during an ACC operation. The British and Americans shared and built upon almost all their techniques throughout the war.

[1] 12th Army Group, Air Effects Committee, and Omar Bradley. Effect of Airpower on Military Operations. July 15th, 1945. 39.

[2] Ian Gooderson. Air Power at the Battlefront: Allied Close Air Support in Europe 1943-1945. (New York, NY: Frank Cass Publishers, 2005), 146-150.

[3] Ibid.,

[4] W. Hays Parks. “Air War and the Law of War.” The Air Force Law Review. 32, no. 1 (1999): 170-208. 199.

[5] 12th Army Group, Air Effects Committee, and Omar Bradley. Effect of Airpower on Military Operations. July 15th, 1945, 42.

[6] Ian Gooderson. Air Power at the Battlefront: Allied Close Air Support in Europe 1943-1945, 85-88.

[7] Ibid.,

[8] Throughout the 20th Century, the blend of interdiction and CAS was constantly reinvented because ACC methodology didn’t live long in official doctrine. In the 80s and 90s, the Army and Air Force reinvented it as Battlefield Air Interdiction (BAI), and in the 21st Century, it was again reinvented as Strike Coordination and Reconnaissance (SCAR).

[9] Headquarters, Tactical Air Command. Tactical Air Power in Support of Ground Forces (Historical). 1986. (Call # K168.04-44 in the USAF Collection, DAFHRA, Maxwell AFB, AL).