Author’s Note: This article covers the first use of the term Tactical Air Control Party in official doctrine. Excuse the poor pictures. FM 31-35 (1946) can only be found at the Air Force Historical Research Center at Maxwell AFB, AL; these are poor scans from that document. In a future trip, a full, high-quality scan of the FM will be conducted.

The US Army, though facing tremendous downsizing and the looming Army Air Forces separation into its own branch of service, did a tremendous job documenting what it did well and what it did poorly throughout WWII. Close air support was one of the hot-button issues of the time, and with the writing on the wall that the AAF would become the USAF in only a matter of months, Army ground force commanders and tactical air commanders rushed to cement close air support in official doctrine. They rightly feared that the new USAF would hyperfocus on strategic bombing and the nuclear mission while allowing close air support (and joint cooperation altogether) to fall by the wayside.

12th Air Force and 9th Air Force compiled hundreds of pages of commentary on the effectiveness or lack thereof of close air support throughout WWII. Interviews spanned the spectrum of time, battlefields, unit type, and opinion, but the overwhelming majority of commanders responded something like, “The close air support we received was great, we ran into occasional issues, and our biggest complaint is that we want more of it.”[1] As such, Army Chief of Staff Gen. Dwight Eisenhower, the most renowned tactical air commander, Pete Quesada, and a select few of AAF elite sought to codify the lessons learned from their time directing joint operations. One of the key steps in that process was to revamp and redistribute Field Manual 31-35, renaming it Air-Ground Operations instead of the old Aviation in Support of Ground Forces (as it had been named in 1942).

The naming convention was to highlight joint equality and cooperation between ground forces and tactical airpower so that future leaders wouldn’t have their sensitive egos struck by an implication that air power was subservient to ground power. Nonetheless, come 1947, the Air Force would do everything it could to solidify its place as the preeminent branch of the US military and subsequently separate itself from joint operations to the maximum extent. The reader can feel the desperate attempt to persuade Air Force generals to comply in the opening explanation of doctrine (see below).

Figure 1: Opening page of the 1946 version of FM 31-35. Note the pleading tone of “each operating under their own command.” In the context of the day, joint fighting advocates had to do everything they could to convince air power advocates that air wasn’t subservient to ground power in order to get them to cooperate. Air power advocates were adamant in fighting for their dominance, and saw cooperation with ground forces as subverting that dominance.[2]

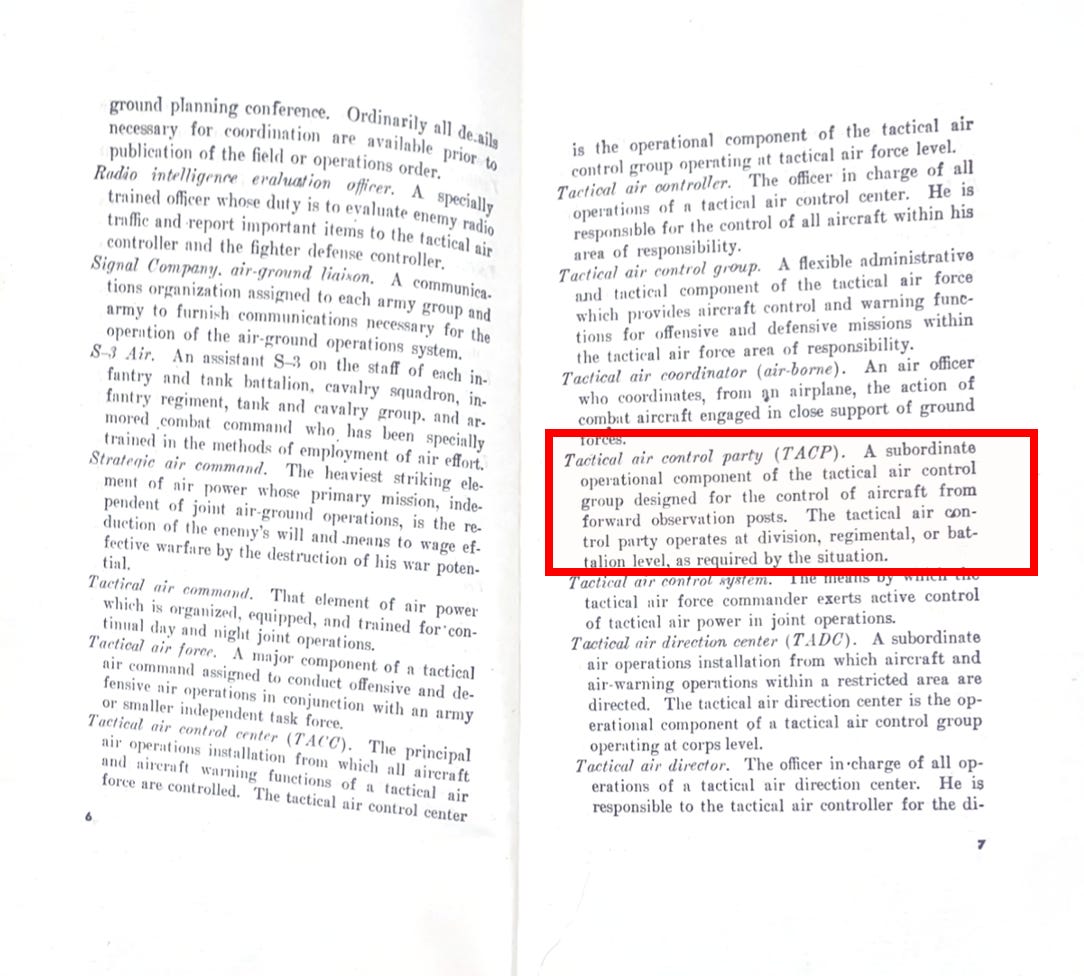

Aside from the point that the joint fighting advocates did what they could appease the air advocates, there was another problem leftover from WWII that needed to be fixed in the new FM 31-35 – terminology. The air-ground doctrine used in WWII was developed on the spot and disseminated across a very large combined/joint force. That wartime development led to different TTPs and significantly different terminology across units. For example, just under 9th Air Force, the three Tactical Air Commands all had different names for their equivalent versions of Air Support Parties and Air Support Party Officers. IX TAC called their version a Tactical Air Party Officers, while XIX TAC called theirs a doctrinally correct Air Support Party Officer, and XXIX TAC called them Tactical Air Liaison Officers. FM 31-35 addressed this issue by standardizing terms. The writers of FM 31-35, likely heavily influenced by a Pete Quesada-led staff, landed on Tactical Air Control Party to replace ASP, and Air Liaison Officer to replace the variations of ASPO.

Figure 2: The first use of Tactical Air Control Party in official doctrine, defined as: “A Subordinate operational component of the tactical air control group designed for the control of aircraft from forward observation posts. The tactical air control party operates at division, regimental, or battalion level, as required by the situation.”[3]

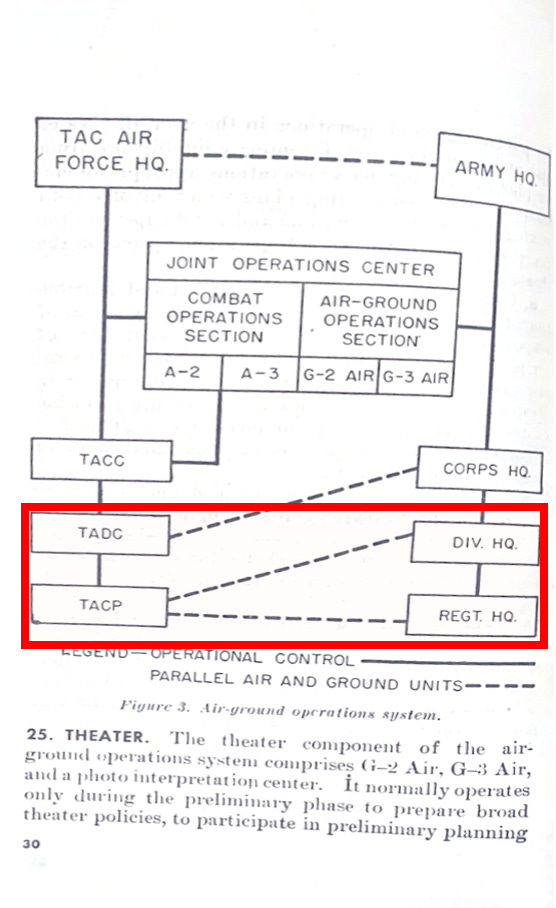

As for the TACP-specific place in overall doctrine, FM 31-35 allowed for flexible employment as the joint commanders saw fit. Note the definition of TACP, which includes the term “as required by the situation.” This became problematic later in Korea when the USAF couldn’t imagine a situation where TACP would be needed below the division level. Even FM 31-35 only displayed TACP as low as the regimental level.

Figure 3: Early version of the air-ground operations system, also defined as the Tactical Air Control System (TACS) in FM 31-35.

Most importantly for the TACP, FM 31-35 defined TACP organization, explained its role in the TACS, and implied suggestions on TTPs. A quick read of the roughly five pages of detail on the TACP tells the reader much. The TTPs suggested are directly reminiscent of WWII tactics, notably the mention of “A Forward Air Controller (FAC) may operate from a tank or armored car at the front of an armored column…” on page 64, showing that the authors certainly had WWII-style Armored Column Cover in mind. While the definitions below certainly leave out a significant amount of important detail, the reader can pick up on quite a few pieces of terminology that were passed on in TACP for generations. Call, Preplanned, and Air Alert missions sound much like modern Preplanned, Immediate, and XCAS missions (pages 66, 67), and the “Methods of Operation” section on page 65 shows the roots of the “Advise, Assist, Control” mindset. Read the below snapshots of FM 31-35 for a full picture of the original layout of the Tactical Air Control Party.

Figure 4: The TACP section starts at the bottom of page 64

Figure 5: Pages 64 and 65. Note the lack of directiveness on where a TACP operates in the Army structure. This became problematic in Korea.

Figure 6: Pages 66 and 67, types of missions and an explanation of the role of the Air Liaison Officer.

It is important to remember that although FM 31-35 provided long-lasting doctrine and terminology that inevitably influenced the use of CAS all the way through the GWOT, the document was written in 1946 when the AAF still lived within the broader Army. One year after the publication of Air Ground Operations, the AAF officially separated from the Army to create the United States Air Force. Few leaders within the new USAF believed in the importance of Air-Ground Operations, and prevailing confidence in nuclear and strategic bombing dominated the new branch. Despite the peacetime efforts by tactical air advocates like Pete Quesada, the first commander of the USAF’s Tactical Air Command, the concepts within FM 31-35 were relegated to the sideline. By the time the USAF needed to fight a purely tactical war in Korea, a few years later, they had shunned FM 3-35 and only maintained barebones requirements for joint fighting with the Army, forcing the USAF and Army to rediscover close air support and the value of the TACP from scratch during wartime.

Author’s Note: The following article will begin the Korea series.

[1] Director, Aerospace Studies Institute, and Lt. Col. Ralph E. Strootman. 5th Army Ground Force Opinion of Air

Support Dec 1944 – Apr 1945. 1945. Call # 680.4501-2 in the USAF Collection, DAFHRA, Maxwell AFB, AL. 1-2, 5.

[2] Department of the Army, FM 31-35: Air-Ground Operations. 1946. (Call # 170.121031-35 in the USAF Collection, DAFHRA, Maxwell AFB, AL). 1.

[3] Department of the Army, FM 31-35: Air-Ground Operations. 1946. (Call # 170.121031-35 in the USAF Collection, DAFHRA, Maxwell AFB, AL). 7.